When we picture the Medieval world, it conjures up images of darkness, privations, and sickness the likes of which are hard to imagine from our sanitized point of view. The 1400s, and indeed the entirety of history prior to the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s, was a time when the merest scratch acquired in the business of everyday life could lead to an infection ending in a slow, painful death. Add in the challenges of war, where violent men wielding sharp things on a filthy field of combat, and it’s a wonder people survived at all.

But then as now, some people are luckier than others, and surviving what even today would likely be a fatal injury was not unknown, as one sixteen-year-old boy in 1403 would discover. It didn’t hurt that he was the son of the king of England, and when he earned an arrow in his face in combat, every effort would be made to save the prince and heir to the throne. It also helped that he had the good fortune to have a surgeon with the imagination to solve the problem, and the skill to build a tool to help.

The Prince

Henry of Monmouth, the future Henry V, was born in 1389 in Wales. His father, Henry Bolingbroke, was cousin to the current king, Richard II, whom he deposed and imprisoned in 1399. Styling himself Henry IV, this put his son Henry, now the Prince of Wales, into the line of succession as heir apparent. As such, great effort was put into grooming him for future kingship, including extensive military training.

Prince Henry’s training was very quickly put to the test at the Battle of Shrewsbury, where King Henry’s men faced the rebel forces of Lord Henry “Hotspur” Percy. The battle marked the first time that English archers faced each other. The English longbow was a terrifyingly powerful weapon, with a draw of 90 to 100 pounds or more; longbows found aboard the wreck of King Henry VIII’s flagship Mary Rose were found to have draw weights of up to 160 pounds. Such a bow would require astonishing upper body strength to draw properly, so much so that the skeletons of English archers show considerable overdevelopment of the bones of the left arm and wrist, as well as the fingers of the right hand.

The Weapon

An English longbow of the era typically was about six feet long, although that varied with the stature of the archer. Arrows typically had thick shafts of poplar, ash, beech, or hazel about 32 to 36 inches long, fletched with goose feathers. Shafts could be fitted with a variety of arrowheads, each specialized to different needs. But the most common warhead at the time was the bodkin point.

A bodkin point was designed to defeat plate armor. Accounts vary on its effectiveness, and modern testing is somewhat equivocal. But the shape of the head, with its square cross-section and sharp edges, was clearly designed to cut through sheet metal. Like most mass-produced metal objects at the time, bodkin points were made from wrought iron. Even with hardening and tempering, this would have left the point too soft to penetrate into the steel plate armor that was becoming more common, but there are historical accounts of bodkin points being “steeled”, which may mean that they were case hardened. This would have been done by wrapping a number of points in charcoal and heating them in a forge to carburize the metal.

Arrowheads of the day were forged with sockets, allowing them to be fitted to the end of a shaft. Methods for attaching the head to the shaft varied; some were glued with hide glue, some were pinned with tiny nails, and others were simply friction fit into the sockets. The latter seems to have been the case with the arrow that found Prince Henry, a stroke of good fortune that would end up helping save his life.

The Battle

The Battle of Shrewsbury was fought on 21 July 1403. Shortly before dusk, King Henry gave the command to attack the Percy forces, and the battle was on. Prince Henry, protected by plate armor and leading his men on the left flank, advanced uphill into the rebel line. The young prince raised the visor on his helmet for a better look at the battlefield, and as luck would have it, an arrow caught him in the face. The bodkin point drove into his left cheek, below his eye and just to the side of his nose. Miraculously, the arrow stopped with about six inches of the shaft embedded in the prince’s face; given the power of a longbow shot at close quarters — easily enough to punch straight through a human skull — it’s likely that the arrow that found Henry was deflected by a shield or someone else’s armor, spending the majority of its kinetic energy in the process.

Despite the agonizing wound, Prince Henry refused to leave the battlefield and kept fighting for three more hours, until Henry Percy suffered a wound ironically similar to Prince Henry’s; when Percy raised his visor to get a breath of fresh air, an arrow, this time unmolested in its flight, found his gaping mouth and killed him. Only then was Prince Henry rushed from the battlefield to nearby Kenilworth Castle, in an attempt to save his life.

The Injury

The fact that the prince was not cut down instantly was a stroke of amazingly good luck. The base of the skull is rich with major blood vessels that supply the brain, important cranial nerves that control basic bodily functions, and the top of the spinal cord, where it exits the skull via the foramen magnum. That the bodkin point threaded between all of these vital structures and lodged itself in the thick, tough bone at the base of the skull, and did so little damage that the prince was able to keep fighting, was nothing short of miraculous.

The royal surgeons knew, however, that the arrow had to be removed. Standard practice at the time was to push the arrow through in the direction that it was going, but being lodged in Henry’s skull, the only option was to pull it out. When surgeons tried this, though, the shaft came free from the arrowhead. It’s not clear if the shaft broke or if it pulled free from the bodkin socket but either way, it left the arrowhead lodged in the prince’s skull at the end of a deep, inaccessible wound.

The Surgeon

At this point, surgeon John Bradmore was sent for. In those days, being a surgeon did not hold the same social cachet as it does today. Surgery was more of a trade than a profession, and surgeons often practiced several different trades in addition to setting bones, amputating limbs, and lancing boils. Bradmore’s other line of work was as a metalworker, a term of trade that connotes the ability to execute finer work than a blacksmith would normally turn his hand to. This was fairly common for surgeons of the day, who often maintained a lucrative sideline making and selling surgical tools of their own design.

Bradmore’s first examinations of Prince Henry, which he recorded in a treatise called the Philomena, involved probing the wound to discover its depth and tract. He reports using the pith from the branches of elder wood as a probe, wrapped in linen and soaked in rose honey — a natural antiseptic. With the position of the bodkin determined, Bradmore proceeded to enlarge the wound with a series of larger diameter probes. This was a necessary if agonizing process; entry wounds often close very tightly after the projectile passes, and Bradmore knew he’d need room to work.

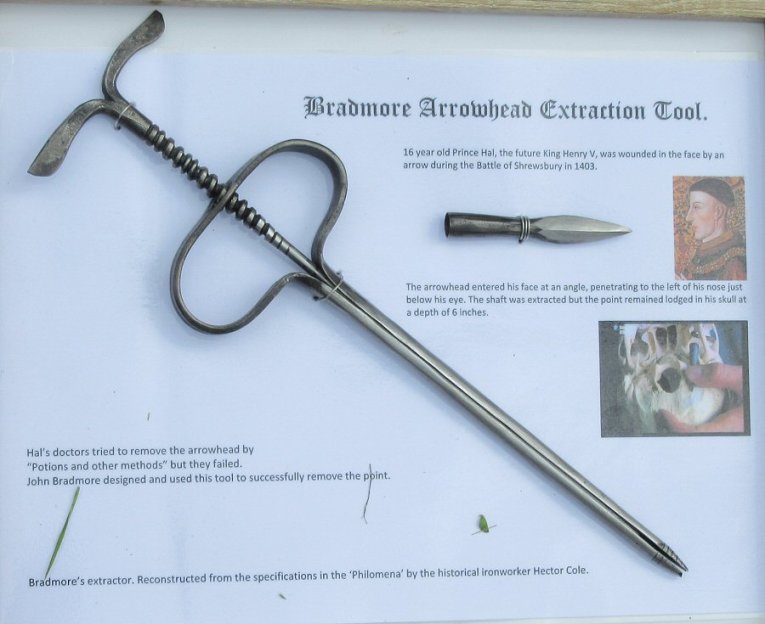

While this slow process of dilatation was going on, Bradmore designed a special set of tongs. In the Philomena, he described it as “[L]ittle tongs, small and hollow, and with the width of an arrow. A screw ran through the middle of the tongs, whose ends were well rounded both on the inside and outside, and even the end of the screw, which was entered into the middle, was well rounded overall in the way of a screw, so that it should grip better and more strongly. This is its form.”

Modern recreations of the tongs require some imagination on the part of the smith, as Bradmore’s description and drawings are somewhat at odds with each other. It could be that the tongs served mainly to guide the central screw into the remains of the shaft; or, if the shaft had pulled out of the bodkin socket cleanly, the tongs could have been forced outward into the walls of the socket by the screw.

Either way, Bradmore was able to grasp the bodkin and, with a little rocking back and forth, removed it from the prince. He filled the wound with white wine, applied a poultice of white bread, flour, barley, honey, and turpentine, and tended to the prince until he healed.

Long Live the King

There’s little doubt that Bradmore saved the future king’s life; a foreign object left in a deep wound would at a minimum lead to septicemia, or, had the arrow driven the anaerobic soil bacterium Clostridium tetani into the wound, a fatal tetanus infection.

For his efforts, Bradmore received a handsome pension for the rest of his life, which was sadly only another nine years. King Henry IV outlived the man who saved his son by a year, leaving the scarred but brave young Prince Henry to ascend the throne in 1413, and eventually go on to win the historic Battle of Agincourt. But none of that would have come to pass had it not been for the luck of a prince and the hacking skills of his surgeon.